Copyright © 2009 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Volume 55, No.3 - Fall 2009

Editor of this issue: Gražina Slavėnas.

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2009 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 55, No.3 - Fall 2009 Editor of this issue: Gražina Slavėnas. |

Jonas Mekas Exhibit: Fragments of Paradise

STASYS GOŠTAUTAS

|

There

are no rules written on the sky… I can show my films on the

screen, I can cut them into pieces and show them as objects or

multi-media installations. Jonas

Mekas

|

| Jonas Mekas and Vytas Goštautas

at an opening of an exhibit on November 13,2008. |

I have been lucky enough to witness the career of Jonas Mekas – artist, “filmer” (Jonas does not consider himself a “filmmaker”), director (Jonas says “I am not a film director because I direct nothing”), critic, archivist, curator, editor, and, of course poet in everything he touches – almost since my first arrival in New York City to start work on my doctoral dissertation at NYU in 1965. That means I was within walking distance of Washington Square and Greenwich Village and Soho, where Jonas, the poet from Semeniškiai, a small village in Lithuania, was trying to force his rebellious will on the American cinema.

80 Worcester Street was then the home of the New American Cinema (NAC), where Jonas would show the dernier cri of the avant-garde for a dollar or less. In 1955, he had founded a magazine called Film Culture, followed by the Film-Makers’ Cooperative in 1962, and, in 1964, the Film-Makers’ Cinematheque, at that time the only place in the universe to show those strange films. Almost at the same time, in 1961, he started his famous column in the Village Voice.The first one reads: “The Creative Joy of the Independent Film–Maker”. The key word here, of course, is “independent” as the opposite of “Hollywood” joy.

Mekas was more than a filmmaker, even though he never abandoned his Bolex or later his Sony video camera. He was a theoretician with a creative gift for the word. He could talk passionately for hours about the then just barely known New American Cinema. He never doubted that each frame would become an art object, and yet he did not foresee that each frame would indeed become a framed picture, each bearing his signature like any other work of art.

That day came not too long ago, and I was impressed by the beauty of those separate stills. They reminded me of Mekas’s sets of poems (in Lithuanian) entitled Pavieniai žodžiai (1967), which in English means something like “separate words,” which he transformed into a single beautiful frame.

Here we go again, I thought, I will be writing another chapter of Jonas’s life, now closer to the end of his search (my first essay was written in 1966 and published in the Spring issue of Lituanus), but it is not the end yet, for he is very much alive and, well, maybe more secure within himself and sometimes more mad than ever.

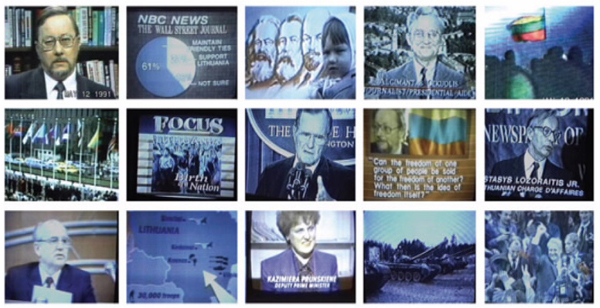

Lately, Jonas Mekas is coming up with new multimedia ideas every year. Ever since he started his association with the Maya Stendhal Gallery in New York City, he has created new strange objects for exhibitions. The last one was a four-monitor video installation entitled “Lithuania and the Collapse of the USSR,” on view from November 13, 2008 through February 21, 2009. “Jumpy and blurry newscast collages,” as noted Manohla Dargis, a film critic for the New York Times – collages that can go back to Picasso and Braque, of course, but always ask for Beauty, another of Jonas’s obsessions. Even if the image is blurry and the sound is poor, they do have poetic insight and force.

Yes, Mekas was right: “There are no rules written on the sky… .” You can do anything you want, of course, if you have talent. To think that you could create art from poor copies taken nightly from television broadcasts takes confidence and daring. And not for an hour or two, but to the exhaustion of four hours and 46 minutes divided among four monitors that run simultaneously presenting the heroes and antiheroes at the end of the communist era. There was M. Gorbachev, and young V. Landsbergis, and K. Prunskienė bravely walking to the White House to meet George H. W. Bush. We all have in our libraries similar poor shots or videos that we copied from TV, but it would never occur to us to actually make a work of art from them as Jonas did.

Jonas can make art from anything. In 2007, he introduced a new kind of diary: a visual diary, or 365 short videos released one per day to be watched every morning on the Internet like news. A short diary with notes and occasional longer comments on life and art were the purpose of this experiment that lasted exactly one year.

But let’s return to the art exhibit called “Fragments of Paradise,” which in some ways is a continuation of another exhibit “this side of paradise” at the gallerie du jour agnès b, Paris, 1999 (please note: no capitals in the original French catalogue). The Paris exhibit is a remarkable visual biography of teenagers John Kennedy, Jr. and Caroline Kennedy during the summers of 1971 and 1972 in France, sometimes accompanied by Jackie Kennedy, at times by her sister Lee Radziwill, but most of the time by their cousins, Anthony and Tina Radziwill. (Incidentally, Radziwill in Lithuanian is Radvila, a famous Lithuanian family that helped govern the Grand Duchy of Lithuania since the seventeenth century.) Jonas’s role with the young Kennedys and Radziwills was that of a summer teacher who entertained and taught them how to use a film camera and make a movie. He even writes down the rules that the young pupils were to follow.

The Paris exhibit is a fragmented

view of the homemade movies shot by

Jonas with the Bolex camera that he never abandoned. The artistic

beauty of the exhibit lies in the fact that Jonas cuts the film strips

into pieces, selects and enlarges them, usually three stills, frames

them, and signs. These are not movies, but rather multimedia objects

that have all the potential of

poetic happiness.

The same idea was adapted and expanded in the exhibition at the Maya

Stendhal Gallery (545 West 20th Street, NYC) from March 3 to May 14,

2005, called “Fragments of Paradise,” which reminds

me of another exhibit in the Spring of 2005, at the Museum of

Contemporary Art (MOCA) in Los Angeles, called *Visual Music*, that

Jonas was not invited to, even though he would have fit there

perfectly, as did his friends from NAC, Stan Brakhage and John and

James Whitney. In that exhibit, five paintings of M. K. Čiurlionis were

exhibited for the first time in the United States, as one of the

precursors of synesthetic art. That same year, Jonas was invited to the

Biennale di Venezia.

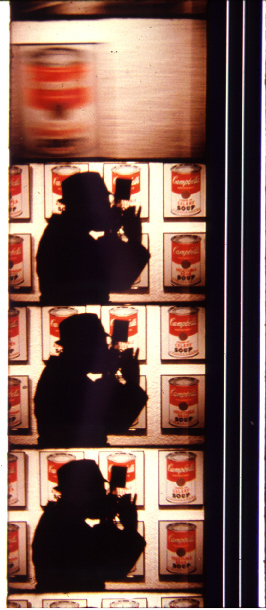

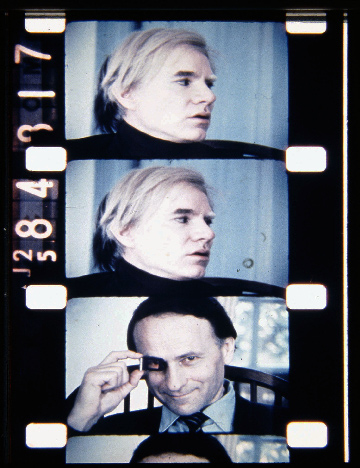

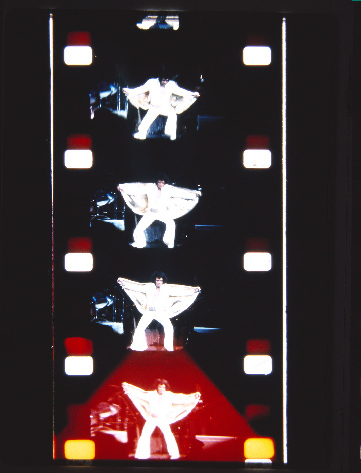

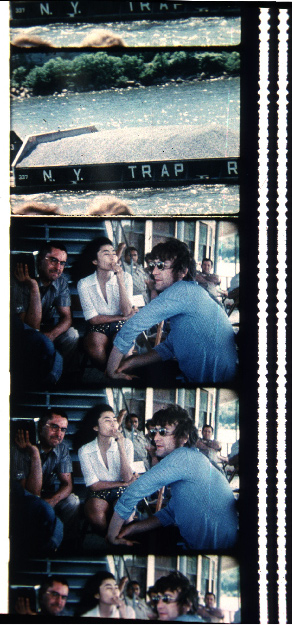

Jonas divides his filmstrips into three or four stills, enlarges them, frames them and signs them. They are pop-art -inspired, and not surprisingly Mekas makes some frames with Warhol and Campbell’s Soup. In another strip, he uses some shots of “George Maciunas, Yoko Ono, and John Lennon. Fluxus trip up the Hudson River, July 1, 1971.” Then, a strange frame of Elvis Presley in white robe or just simply a flower on his window. But let’s see what Jonas himself says about what he calls “frozen film frames”:

Now, why am I making these prints, which I usually call “frozen film frames”? Not for money, of course, since very few of them have sold. I am making them because I am obsessed with the possibilities of having two, three frames/images together, detaching them from the context and letting them be by themselves. I am not collaging them now, of course, they were collaged by my single frame filming technique during the moment of filming. Thus they are not calculated collages but spontaneous collages done during the intense moments of filming. They do one thing when they are in the film and they become completely something else when they are detached and enlarged and framed and presented in a gallery situation. The fact that these are film frames remains always present in the viewer’s mind & eye since I keep in the print the sound track and anything else that could be in the strip of the film from which the print is made.

The exhibit did not have a catalogue, probably because there were too many different objects there. To prove the point that everything could be part of this exhibit, Jonas created several Fluxus situations, like “Memorabilia of Jonas Mekas,” where he writes haiku graffiti on the wall while on the floor there are strips of film, paper, photographs, notebooks, etc. Another Fluxus creation is called “Rillettes.” This time he uses a closet to damp film strips, pieces of paper, written and erased poetry. I do not know what this part of the show has to do with “Fragments of Paradise,” but it is possible that Jonas wanted to be sure that he was part of Fluxus, too. Let him explain this strange creation, based on a memory of his mother:

Usually, when I edit my films and begin to splice the various pieces together, I cut off a frame or two from the ends of each piece – they are usually damaged or otherwise un-spliceable – and throw them on the floor. All filmmakers do that. But that late night in 2000, while editing “As I was moving ahead,” I looked down at the hundreds and hundreds of little ends and pieces of film on the floor and suddenly a scene from my childhood came to my memory. Before big holidays, usually before Christmas, my father and older brothers used to slaughter a pig. And it was Mother who cut the pig into pieces and did whatever they did with the meat – she did it well. After everything was done and stored away, there were all kinds of miscellaneous little pieces left over. She used to collect all of them, put them into a big clay pot, and place it into our big clay oven. It cooked there, on a slow fire, for hours and hours, sometimes days. The result was this incredible stuff that you spread on bread and, ah, it tasted heavenly! Now, the French still do that, and they call it rillettes.

So as I was contemplating and remembering all that, I suddenly thought: my mother never threw away anything, so why am I throwing away these little pieces of film? So I collected them into a film can and put it on the shelf. A few days later I looked at the little pieces and I decided to place them into slide covers and produce slides from them. I made some five hundred slides from these pieces and, of course, I call them rillettes. They are related to the film, but they do not appear in the film because I cut them off. So they are now something independent and different.

Now, at age 87, Jonas Mekas can afford to play with art and poetry, and usually he plays very seriously. Presently, he is engulfed in a Guggenheim project in Vilnius, a fascinating idea if it ever comes to fruition. He plans to house his Fluxus collection, which he sold to the city of Vilnius, there.

Jonas’s latest show, hosted

by Maya Stendhal Gallery, which

ended on April 18, 2009, was another film event, this time to raise

money for the “Anthology Film Archives: Looking

Forward” (founded in 1970). It also pays a Tribute to Jerome

Hill, one of the earliest and for some years the sole partner of Jonas

in the Film Archives, which over the last forty years became the

largest repository of avant-garde film and video, and now probably

DVDs, in the world. As I understand it, Jonas is looking for a new home

for his Anthology.

|

| Lithuania and the collapse of USSR, 2008. |

|

| Warhol show at Whitney. May 1971. From “Scenes from the Life of Andy Warhol.” |

|

| Jonas Mekas and Andy Warhol |

|

| Elvis Presley. |

|

| George Maciunas, Yoko Ono, John Lennon. Fluxus trip up the Hudson River, July 1, 1971. |